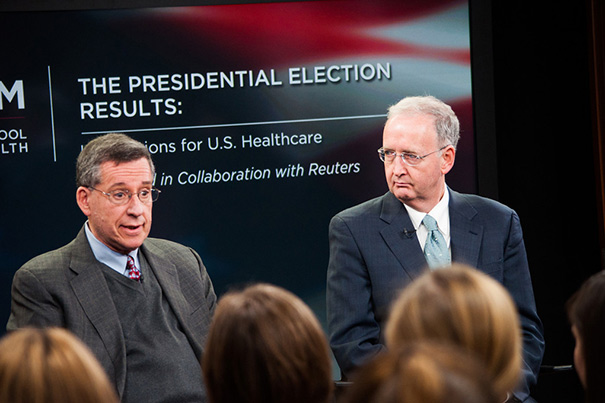

Although some parts of the Affordable Care Act are already active, Professor of Health Policy and Political Analysis Robert Blendon (left) believes implementation will be uneven from state to state. “The important thing is the law moves forward and survives,” said John McDonough (right), director of HSPH’s Center for Public Health Leadership.

Photos by Aubrey LaMedica/Harvard School of Public Health

Green light for Obamacare

HSPH panelists assess road ahead, including potential bumps

After three major scares, President Obama’s health care reform law is now part of the nation’s legal and health care landscape, Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH) panelists said Thursday, though its effects will vary depending on where you live.

John McDonough, director of HSPH’s Center for Public Health Leadership and a professor of the practice of public health, outlined the law’s close calls. The first came with the death of Sen. Edward Kennedy, a longtime champion of reform, and his replacement by Republican Scott Brown, who opposed the law. The second was the Supreme Court challenge, which was upheld in June, and the third was Tuesday’s presidential election, which some saw as a national referendum on health care and other major initiatives of Obama’s first term.

“The important thing is the law moves forward and survives,” said McDonough, who between 2008 and 2010 was a senior adviser on national health reform for the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions.

The Forum at Harvard School of Public Health event, co-sponsored by HSPH and Reuters, was moderated by Reuters Washington health care correspondent David Morgan and also featured Professor of Health Policy and Political Analysis Robert Blendon, Professor of Health Economics Katherine Baicker, and Arnold Epstein, professor of medicine, Foster Professor of Health Policy and Management, and chair of HSPH’s Department of Health Policy and Management.

While opponents’ hopes to repeal the law died with Obama’s re-election, significant implementation challenges remain, panelists said. States that had been dragging their feet pending the election’s outcome have to create statewide “exchanges” where small businesses and individuals can purchase health insurance at a discount before the law’s mandated coverage provisions go into effect in 2014.

Although some parts of the Affordable Care Act are already active, such as the provision allowing parents to keep children on their health insurance plans until they’re 26, others will take effect in the next few years. Among them are the two major ways the law extends coverage to some 30 million uninsured: an expansion of Medicaid to provide health insurance to more of the nation’s poor, and the individual mandate requiring individuals to purchase health insurance or pay a penalty. The state insurance exchanges, together with federal subsidies, are intended to provide lower-cost alternatives to those seeking insurance because of the mandate.

Implementation will be uneven from state to state, Blendon said. States have discretion to design and implement their own insurance exchanges and even to refuse to do so. Some of the 30 states headed by Republican governors will likely not set up exchanges, Blendon said, which means the federal government can step in to do so.

“The U.S. has a national health plan, but what it looks like two years from now will be a matter of politics,” Blendon said.

McDonough pointed out that Congress still has to approve funding for the law, providing a backdoor way for opponents to try to weaken it. That’s a particular hazard, he and Blendon said, with lawmakers expected to quickly ramp up discussions over federal budget deficits because of the “fiscal cliff” of automatic tax increases and spending cuts looming at the end of the year.

After years out of the spotlight, Medicaid, the 47-year-old state-federal program that provides health benefits for the poor, is likely to become a significant part of the political debate because of its central role in expanding health care coverage, McDonough said.

While the law is designed to expand coverage to millions of uninsured Americans, another goal is to curtail rising health care costs, something that is much harder to do, Baicker said. Key to attaining that goal, she said, will be flexibility, because unlike expansion of health insurance coverage — which Baicker said we know how to do — cutting costs is “much thornier,” with success requiring experimentation.

“I hope there’s room for modification going forward as we see what works and what doesn’t,” Baicker said.

It’s important for policymakers to distinguish between costs related to expanding care and the increased costs of providing the same care, Baicker said. For the latter, she said, the act contains provisions for a number of pilot programs that can provide models if they are successful at containing costs. Increased preventive care, for example, coupled with an emphasis on exercise and nutrition, can bear fruit, as shown by European systems where people are treated earlier in an illness’s course.

“We enter the health system in much worse shape than our European counterparts,” Baicker said.

One example might be right here in Massachusetts, which passed a law aimed at containing health care costs in August, Epstein said.

“I think the next four years will be a period of experimentation,” Epstein said.