Larry Benowitz and colleagues at Boston Children’s Hospital showed that a three-pronged intervention can restore some elements of vision in mice blinded by severe optic nerve damage: depth perception, optomotor response, and synchronized circadian activity.

Graphic courtesy of Boston Children’s Hospital

Scientists restore basic vision in lab mice

Findings suggest hope for patients with glaucoma, optic nerve damage

Researchers have long tried to get the optic nerve to regenerate when injured, with some success, but no one has been able to demonstrate recovery of vision. A team at Harvard-affiliated Children’s Hospital reports a three-pronged intervention that not only got optic nerve fibers to grow the full length of the visual pathway (from retina to the visual areas of the brain), but also restored some basic elements of vision in live mice.

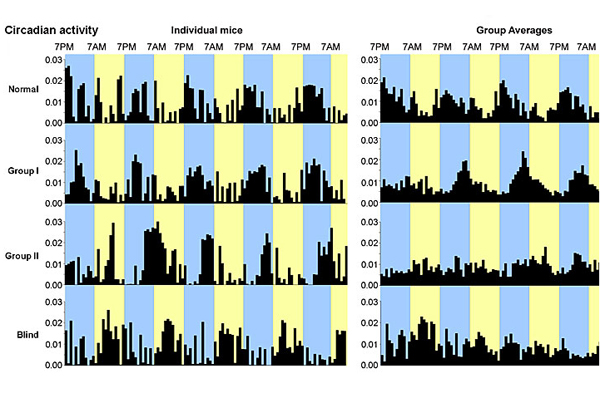

Larry Benowitz, a professor of surgery and of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School, and colleagues at the F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center at Harvard-affiliated Children’s Hospital showed that mice with severe optic nerve damage can regain some depth perception, the ability to detect overall movement of the visual field, and perceive light, allowing them to synchronize their sleep/wake cycles.

The findings, published online by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, hint that those blinded by optic nerve damage from trauma or glaucoma, conditions affecting more than 4 million Americans, might be able to regain at least some visual function. In other forms of vision loss, such as macular degeneration, people can sometimes regain visual acuity, but there is currently no way to recover from damage to the optic nerve.

Previous studies, including many by the Benowitz lab, have demonstrated that optic nerve fibers can regenerate some distance through the optic nerve, but this is the first study to show that these fibers can be made to grow long enough to go from eye to brain, that they are wrapped in the conducting “insulation” known as myelin, that they can navigate to the proper visual centers in the brain, and that they make connections (synapses) with other neurons, allowing visual circuits to re-form.

“Dr. Benowitz and his group have, for the first time, established proof-of-concept that a damaged optic nerve can regenerate and attain lost function,” says Nareej Agarwal, of the National Eye Institute, which supported the study. “This is an important advance in an effort to reverse vision loss in glaucoma and other neurodegenerative diseases.”

Building on their previous studies, Benowitz and colleagues combined three methods of activating the growth of retina neurons, known as retinal ganglion cells. They stimulated a growth-promoting compound called oncomodulin, originally discovered in the Benowitz lab in 2006, elevated levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), and deleted the gene that encodes the enzyme PTEN. In a 2010 paper, Benowitz and colleagues showed that these interventions have a synergistic effect on growth of optic nerve fibers.

“Sixteen years ago, people said it was impossible to get any regeneration in the optic nerve,” said Benowitz, who is also director of the Laboratories for Neuroscience Research in Neurosurgery at Boston Children’s Hospital. “Our study regenerated only a small percentage of the total number of fibers that would normally come into the brain, but it answers questions that have been real unknowns in the field.”

Benowitz cautions, however, that the vision the mice regained was limited, and probably didn’t restore the ability to discriminate objects.

“What lies behind what we call seeing is very complicated — so many subsystems contribute to seeing,” he said. “We’re in a sense just scratching the surface about functional recovery.”

The molecular manipulations performed in the mice would need to be adapted to create an actual treatment for patients, Benowitz said. He hopes to investigate a gene-therapy approach in the future; such an approach has been proven to work in Leber’s hereditary neuropathy, a rare genetic disease causing vision loss.

“The eye turns out to be a feasible place to do gene therapy,” Benowitz said. “The viruses used to introduce various genes into nerve cells mostly remain in the eye. Retinal ganglion cells are easily targetable.”