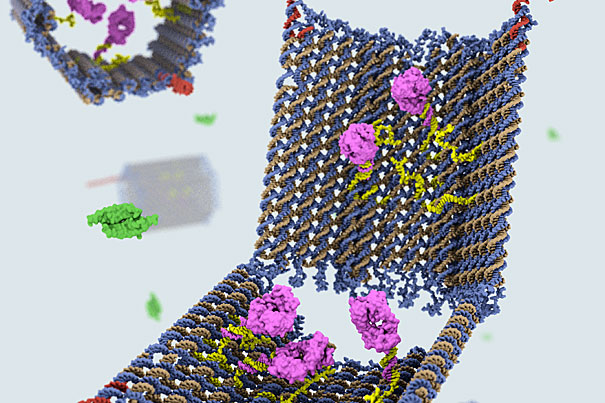

The nanosized robot was created in the form of an open barrel whose two halves are connected by a hinge. The DNA barrel, which acts as a container, is held shut by special DNA latches that can recognize and seek out combinations of cell-surface proteins, including disease markers. This image was created by Campbell Strong, Shawn Douglas, and Gaël McGill using Molecular Maya and cadnano.

Image courtesy of the Wyss Institute

Sending DNA robot to do the job

Technology has potential to seek out cancer cells, cause them to self-destruct

Researchers at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University have developed a robotic device made from DNA that could potentially seek out specific cell targets within a complex mixture of cell types and deliver important molecular instructions, such as telling cancer cells to self-destruct. Inspired by the mechanics of the body’s own immune system, the technology might one day be used to program immune responses to treat various diseases. The research findings appear today in Science.

Using the DNA origami method, in which complex 3-D shapes and objects are constructed by folding strands of DNA, Shawn Douglas, a Wyss Technology Development Fellow, and Ido Bachelet, a former Wyss postdoctoral fellow who is now an assistant professor in the Faculty of Life Sciences and the Nano-Center at Bar-Ilan University in Israel, created a nanosized robot in the form of an open barrel whose two halves are connected by a hinge. The DNA barrel, which acts as a container, is held shut by special DNA latches that can recognize and seek out combinations of cell-surface proteins, including disease markers. When the latches find their targets, they reconfigure, causing the two halves of the barrel to swing open and expose its contents, or payload. The container can hold various types of payloads, including specific molecules with encoded instructions that can interact with specific cell surface signaling receptors.

Douglas and Bachelet used this system to deliver instructions, which were encoded in antibody fragments, to two different types of cancer cells — leukemia and lymphoma. In each case, the message to the cell was to activate its “suicide switch” — a standard feature that allows aging or abnormal cells to be eliminated. And because leukemia and lymphoma cells speak different languages, the messages were written in different antibody combinations.

This programmable nanotherapeutic approach was modeled on the body’s own immune system in which white blood cells patrol the bloodstream for any signs of trouble. These infection fighters are able to home in on specific cells in distress, bind to them, and transmit comprehensible signals to direct them to self-destruct. The DNA nanorobot emulates this level of specificity through the use of modular components in which different hinges and molecular messages can be switched in and out of the underlying delivery system, much as different engines and tires can be placed on the same chassis. The programmable power of this type of modularity means the system has the potential to one day be used to treat a variety of diseases.

“We can finally integrate sensing and logical computing functions via complex, yet predictable, nanostructures — some of the first hybrids of structural DNA, antibodies, aptamers, and metal atomic clusters — aimed at useful, very specific targeting of human cancers and T-cells,” said George Church, a Wyss core faculty member and professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, who is principal investigator on the project.

Because DNA is a natural biocompatible and biodegradable material, DNA nanotechnology is widely recognized for its potential as a delivery mechanism for drugs and molecular signals. But there have been significant challenges to its implementation, such as what type of structure to create; how to open, close, and reopen that structure to insert, transport, and deliver a payload; and how to program this type of nanoscale robot.

By combining several novel elements for the first time, the new system represents a significant advance in overcoming these implementation obstacles. For instance, because the barrel-shaped structure has no top or bottom lids, the payloads can be loaded from the side in a single step — without having to open the structure first and then reclose it. Also, while other systems use release mechanisms that respond to DNA or RNA, the novel mechanism used here responds to proteins, which are more commonly found on cell surfaces and are largely responsible for transmembrane signaling in cells. Finally, this is the first DNA-origami-based system that uses antibody fragments to convey molecular messages — a feature that offers a controlled and programmable way to replicate an immune response or develop new types of targeted therapies.

“This work represents a major breakthrough in the field of nanobiotechnology as it demonstrates the ability to leverage recent advances in the field of DNA origami pioneered by researchers around the world, including the Wyss Institute’s own William Shih, to meet a real-world challenge, namely killing cancer cells with high specificity,” said Wyss Institute Founding Director Donald Ingber. Ingber is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and the Vascular Biology Program at Children’s Hospital Boston, and professor of bioengineering at Harvard’s School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. “This focus on translating technologies from the laboratory into transformative products and therapies is what the Wyss Institute is all about.”