Internet, the sequel: The Web of Academe

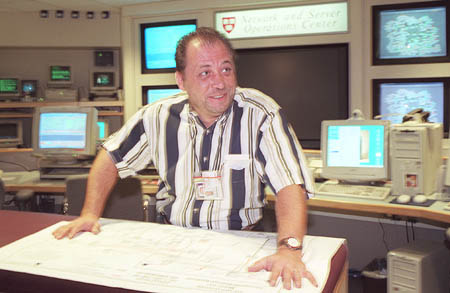

A giant computer screen, flanked by smaller monitors, dominates the basement room on Cambridge Street, giving the impression you’re in Harvard’s version of Mission Control.

You’re not. You’re in the control room for Harvard’s computer network and one of the control centers for a new Internet that’s abroad in the land – or at least in the academy.

Instead of images of shuttles taking off and landing, the screens show images of computer networks – simple squares joined by lines that represent the connections between different computers across campus.

From here, Harvard runs our little corner of the new Internet.

Harvard has been connected to the latest and greatest computer network, dubbed Abilene, since August. Abilene is a new computer network that is part of Internet 2, an attempt by research institutions to create a larger dedicated network that will allow rapid communication between them.

The current Internet began as such a network – albeit much slower – but today has become heavily trafficked by commercial and personal communication, from e-mail to Web surfers to distance-learning students watching video lectures.

“This is, ironically, re-creating for the research community what the original Internet was supposed to be,” said Daniel Moriarty, Harvard’s assistant provost and chief information officer.

Even before Harvard was connected to the new Internet, though, its computer personnel has handled the Northeastern hub of Internet 2, making sure the connections among universities across the region stay up and running.

Internet 2, created with the latest and greatest in fiber optic cables, network routers and other types of computer equipment, is intended to facilitate communication between researchers at different institutions. It does this by providing a relatively traffic-free route so researchers can exchange huge amounts of data, letting a researcher here, for example, tap into another university’s video archives and download a rare piece of footage. And medical researchers could exchange computer-constructed three-dimensional models of proteins much more quickly than they could via the commercial Internet.

“Over the commercial Internet, you either couldn’t do [such things] or it would take forever,” said Leo Donnelly, senior technical consultant for University Information Systems (UIS).

And, though Internet 2 does incorporate the latest technology, it’s the lack of traffic and the more direct connections between member institutions that make the difference. In the arms race that is today’s computer world, much of the equipment in the traditional Internet is as advanced as that in Internet 2.

“Basically, it’s providing a dedicated network for university users,” said H.T. Kung, the William H. Gates Professor of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering.

Kung got a taste of what’s possible with the new network about a year and a half ago, when he taught computer science to two classes at the same time – one here and one at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

The class, which Kung team-taught with Carnegie Mellon instructors, was conducted in real time, with students in both classes listening to lectures and asking questions via a video hookup. The connection was made over another Internet 2 network, called vBNS, which stands for “very high performance backbone network service.”

But Kung said one thing that teaching that class showed him is that for things such as distance learning, the technology is already adequate. More attention has to be focused not on equipment, but on things like production. The biggest problems he experienced in teaching that class wasn’t the speed of the hookup or glitches with the computer gear, rather it was things like making sure the mike was turned on and that the volume was turned up enough.

So, how do you get on Internet 2? Relax, you’re already on it.

Or you are if your e-mail, Web page, or other Internet traffic is heading to another Internet 2 member, Donnelly said.

The switch to Internet 2 happens automatically, inside a computerized box called a router. A router is nothing more than a fancy traffic cop making sure Internet traffic gets where its going. The router automatically checks the destination, ships regular traffic out via the commercial Internet, and routes traffic to other Internet 2 institutions over Internet 2.

That means everything from e-mail headed to the University of California at Berkeley to those giant 3-D molecular models being exchanged with a researcher at Johns Hopkins goes over Internet 2.

“We have researchers today whose data is going via Internet 2 and they don’t know it,” Moriarty said.

But that doesn’t mean it all goes lightning-fast, Donnelly said.

Internet 2, like many things, is only as good as its weakest link, he said. That means that if a computer server at Johns Hopkins is old and slow, it doesn’t matter how fast Harvard’s computers are or even how fast Internet 2 is. Traffic will only move as quickly as that slowest link will let it.

In fact, in order to ensure that it won’t be Harvard’s end that is slowing things up, the University has been involved in an ongoing process of upgrading computer and computer network equipment. In addition to its Internet 2 hookup, Harvard recently tripled the size of its connection to the commercial Internet, from 45 megabits per second to 155 megabits per second.

“Harvard’s Internet traffic is growing 20 to 30 percent per year and there’s no end in sight,” Moriarty said. “We keep thinking this is the year it will level off, but it never does. … Our best estimate now is that the Harvard community, without the affiliated hospitals, sends about a half a million e-mails a day. We also make 38,000 phone calls per day, and it’s not that phone calls are way down.”

With a computer network the size of Harvard’s, Donnelly said it wasn’t surprising that Harvard was chosen to manage the Internet 2 hub in New England. That hub is physically located at Downtown Crossing in Boston, but is managed remotely from the Cambridge Street control room. That hub collects traffic from member schools in the Northeast and sends it out via Internet 2 or via the attached commercial connections, depending on its destination.

By managing the hub, Harvard may have taken on a bit more work, but it is getting invaluable experience, Donnelly said.

“We’re one of the largest private networks in the United States, mainly because of the teaching hospitals behind us,” Donnelly said. “One reason we wanted to do it is it exposes our engineering staff to new technology. For us it’s a precursor of what we’re some day going to be doing internally.”

As for the future, both Moriarty and Donnelly agree that the pace of technological change will only accelerate in the coming years. Unlike the original Internet, Internet 2 will remain dedicated to university and government research institutions. What is being sent over those wires is likely to change, they said, as software applications that can truly take advantage of the network’s speed are developed. Video conferencing, computerized telephone networks, and high definition television streaming 300 megabits per second (more than 5,000 times faster than a 56k modem) of video images aren’t far off.

What’s amazing, Moriarty said, is the seemingly limitless appetite of the Harvard community for new technology. Each new device, each laptop, cell phone, or Palm Pilot that comes along, seems not to replace old items, but to fit nicely into a new niche.

“In our academic community, the capacity to absorb new technology … is just about boundless,” Moriarty said.

For more information on Internet 2, go to http://www.internet2.edu/ or http://www.nox.org/ on the Web.