Care for Glass Flowers branches out

Natural History Museum’s fragile flowers get needed cleaning and repair

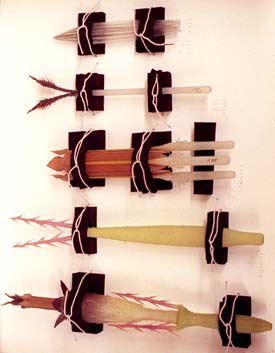

The Glass Flowers – Harvard’s majestic collection of more than 4,000 botanical models – is proof that the marriage of art and science is not only possible, but something quite extraordinary. Called “the Sistine Chapel of the glass world,” by Susan Rossi-Wilcox, curatorial associate at Harvard’s Museum of Natural History, the models also happen to be an educational tool spanning 100 years and several disciplines.

In 1886, Professor George Lincoln Goodale of the Botanical Museum commissioned German glass artisans Leopold Blaschka and his son, Rudolph, to create realistic-looking lilies, pines, cacti, and fungal bodies, among others – totaling 847 species and plant varieties. The project continued until 1936. Because of their anatomical precision – which has made them extremely delicate – the Glass Flowers remain a teaching device to this day. “Before a big exam,” notes Rossi-Wilcox, “students still come in to double-check.”

Sadly, it is the same fragility of these models, needle-thin “roots” for instance, coupled with their immense popularity, that has left the specimens susceptible to damage and stress. With 120,000 visitors traveling through the museum each year, the Glass Flowers have been subject to harmful vibrations. Ultraviolet light has also taken its toll on the models, despite the museum’s efforts to block ultraviolet rays. A few models, some of which are over 100 years old, are also beginning to succumb to corrosive “glass disease” – chemical stresses inherent in the materials – causing cracks and discoloration.

Since 1998, the museum, led by Joshua Basseches, executive director, has been engaged in an effort to halt future deterioration and repair existing damage, where possible. With the initial phase of moving the first batch of Glass Flowers from their precarious cases complete, the models await transport to an off-site conservation and storage facility. From there, the daunting task of 15,000 conservation hours remain, and even that’s a bare-bones estimate, according to Rossi-Wilcox.

Throughout the restoration effort, the majority of the collection will continue to be on display for glass enthusiasts, botanists, and everyone in-between. The Harvard Museum of Natural History is located at 26 Oxford St. and is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. For more information call (617) 495-3045.