Water power: Once American women rowers trailed the field. In 1975, that all changed.

If you had been walking along Memorial Drive early one particular morning during the summer of 1975, you might have seen a group of strapping young women expertly lowering a long eight-seat shell into the water from the dock of Newell boathouse. A common enough sight, except that in a short while these women would do something that had never been done before, something that would have a huge impact on American women’s athletics.

At the World Championships in Nottingham, England, this crew of American women rowers would capture the silver medal, losing by a hair to the East Germans, state-supported athletes groomed and trained since childhood who, many contend, would never have passed the rigorous drug testing of today’s international competitions. American male rowers had always been tops at their sport, but before Nottingham, no American women’s team had ever come close to finishing among the top three.

The women’s spectacular upset (they finished well ahead of formidable teams like the Russians and Rumanians) brought them sudden media attention and, like the American women soccer team’s victory at the World Cup in 1999, their performance forced people to change their opinion about what American women could accomplish in athletics.

It also helped to pressure many college programs in rowing and other sports to comply with the recently passed Title IX legislation, which mandated that equal amounts of money be spent on women’s and men’s athletics.

Some schools that did not move fast enough were shamed into action. Anne Warner and Chris Ernst, Yale students who had helped stroke the American boat to its silver medal finish, found that when they returned to school, the athletic department still treated them like second-class citizens. The Yale boathouse was a 40-minute drive from campus, and, while male rowers were given facilities to shower after practice, the women had to drive back in their sweaty workout gear.

To make their point to an unresponsive athletic department, Ernst and Warner staged a “strip-in,” reported by The New York Times and the Associated Press. Standing in the athletic director’s office and flanked by a small army of supporters, the two women calmly removed their sweatsuits to reveal the words “Title IX” written in Magic Marker across their naked chests and backs. Following an outcry from Yale alumni, the University complied with the women’s demands.

Daniel Boyne, director of recreational rowing at Harvard, learned about the women’s performance at the World Championships when he was assigned to write a profile of Gail Cromwell Pierson, a member of the 1975 team. Pierson, the team’s oldest rower, had also been the first woman to row a single scull in the Head of the Charles Regatta and the first woman to teach in Harvard’s Economics Department.

Boyne, a writer as well as a rower, was no stranger to women’s achievements in the sport. He had been introduced to rowing by his older sister who rowed at Mount Holyoke. Later, he rowed competitively at Trinity College and, in the 1980s, coached women’s crew at Tufts. The women’s achievement at the 1975 World Championships not only seemed like a story that needed telling, it also struck Boyne as an opportunity to bring to life the beauty and complexity of the sport he loved.

“This was a total ‘Bad News Bears’ story,” he said. “A crew is thrown together, they train for six weeks, then go to England and nearly win it all.”

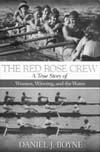

Boyne titled his book “The Red Rose Crew: A True Story of Women, Winning, and the Water” (Hyperion, 2000). The women took that name after a supporter tied a red rose to the laces of each of their rowing shoes just before the final race at Nottingham.

The book abounds in colorful details and subtly drawn portraits. Boyne follows several of the women as they search for a way to channel the energy and competitiveness that the male-dominated society often labels unfeminine.

There is Pierson, already a champion in several sports as well as an accomplished scholar by the time she joined the team. Carie Graves, a rebellious college dropout, wandered through Europe and posed as an artist’s model before she discovered that pulling on an oar could help her exorcise her self-defeating demons.

“This was a collection of individuals who were desperate to prove themselves and to do something powerful, and rowing allowed them to do it,” Boyne said.

Boyne interviewed all nine women of the Red Rose Crew, the eight rowers and the coxswain, Lynn Silliman, building up details and comparing one story with another to arrive at the most accurate version of events.

He also talked to the women’s coach, Harry Parker, now in his 40th year of coaching men’s heavyweight crew at Harvard. The famously taciturn Parker yielded little in the way of personal details, but Boyne managed to weave together stories from the women and others to paint a portrait of a reserved, intense man, dubious at first about his unaccustomed role, but gradually won over by his crew’s enthusiasm and willingness to endure the pain of all-out training.

The book often reads like a novel, and the story it tells is the classic one of underdogs coming from behind to capture the prize, but in addition to the human story this is also a book about a sport, and a rather arcane one at that.

Boyne is skillful in the way he introduces details about things like rigging and sliding seats, the fine points of the stroke, and the different role by each of the eight positions.

There is also considerable information about the history of rowing. We learn that Jack Kelly (whose daughter, Grace, would later become a Hollywood star and Princess of Monaco) was not permitted to race in England because he was a bricklayer, and that by tradition the starter sends the crews off in French. By the end of the book we find that we are well on our way to becoming connoisseurs of a sport that was little more than a flat picture in our minds when we began.

We also learn something about the nature of rowing and the kind of rewards it offers its devotees. It is not, Boyne admits, a sport that requires skills on the level of basketball or gymnastics, although a smooth, efficient stroke is something that comes only after much experience.

“It’s a sport where willpower can be channeled most easily, given a certain minimal level of skill,” he said. “That’s one of the most appealing things about it. If you’re willing to work really hard, you will find a place in rowing.”

The members of the Red Rose Crew not only found a place in rowing, but in rowing history as well.

Boyne, who has published articles about rowing in several periodicals, is also the author of “Essential Sculling” (The Lyons Press, 2000). On Oct. 21 at 6 p.m., he will read from “The Red Rose Crew” at Wordsworth Bookstore in Harvard Square.