Sophomore skips orientation to free 4,000 slaves in Sudan

As Harvard sophomore Jay Williams passed through customs and trudged toward the exits at Terminal E in Logan Airport two weeks ago, the colorful images reflecting off his sunglasses proclaimed the enormity of the moment. Just seconds after emerging from the international gates, the 19-year-old religion and pre-med concentrator was surrounded by reporters, photographers, fellow students, and supporters — all anxious to hear his dramatic story.

Williams had just returned from Sudan, where, as part of a six-person delegation, he spent a week in the northern African country helping to free more than 4,400 slaves — mostly women and children allegedly taken by force from their families and villages during the nation’s brutal civil war.

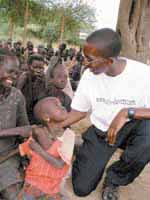

Harvard sophomore Jay Williams returned to Boston from Sudan earlier this month where he was part of a six-person delegtation that traveled to Northern Africa. Williams, who was an intern with the American Anti-Slavery Group in Washington, D.C. worked with redeemers in Sudan to buy slaves, mostly woman and children. The cost per human: $33. Sudan photos courtesy of the American Anti-Slavery Group and Christian Solidarity International

Harvard sophomore Jay Williams returned to Boston from Sudan earlier this month where he was part of a six-person delegtation that traveled to Northern Africa. Williams, who was an intern with the American Anti-Slavery Group in Washington, D.C. worked with redeemers in Sudan to buy slaves, mostly woman and children. The cost per human: $33. Sudan photos courtesy of the American Anti-Slavery Group and Christian Solidarity International  Calling his experience “absolutely unbelievable,” Williams gave a firsthand account of life in a troubled land. “To see an entire people, an entire culture, just uprooted and destroyed by such a terrible event that’s been going on for years and years, it was heartbreaking,” he said.

Calling his experience “absolutely unbelievable,” Williams gave a firsthand account of life in a troubled land. “To see an entire people, an entire culture, just uprooted and destroyed by such a terrible event that’s been going on for years and years, it was heartbreaking,” he said.

Sudan is a nation that has been ripped apart by the war for more than a decade. An estimated 1.5 million people have lost their lives in the fighting and the accompanying famine. Millions of others have been displaced from their homes, escaping the violence breaking out around them.

Sudan is a nation that has been ripped apart by the war for more than a decade. An estimated 1.5 million people have lost their lives in the fighting and the accompanying famine. Millions of others have been displaced from their homes, escaping the violence breaking out around them.

According to the Boston-based American Anti-Slavery Group, as many as 100,000 Sudanese have been forced into slavery by militant Arab-Muslim forces based in the north intent on exacting revenge against black Christians and animists in the south.

“They swoop in and kill the men. Then they burn the villages,” said Jesse Sage ’98, the organization’s associate director. “They take the women and children, strap them to horses, rope them by the neck, and take them north.” There, the victims are allegedly forced into lives of servitude — many of the women are raped, while the children are put to work in the fields and homes of their masters.

Williams first learned of the dire situation in Sudan last December, when he attended a local gospel concert, which happened to be a fundraiser for the American Anti-Slavery Group. The Buffalo, N.Y., native was astounded with what he heard that night.

“I just couldn’t help but get involved,” Williams said. “Quite simply, there’s still slavery in the world. It’s the year 2000! We’ve advanced so far, but there’s still one of the most primitive forms of human existence in the world, and I have to do everything that I can to help bring it to an end.”

While working as an intern for the American Anti-Slavery Group in Washington, the opportunity arose for Williams to become directly involved in the crisis, when he was asked to accompany five others on a “slave redemption” mission to Sudan. “I knew at that instant that I’d be going. I just had that feeling,” Williams relates. “I was a little bit nervous, but I knew that I’d be going.”

“This is a very dangerous trip,” said Charles Jacobs ’88, co-founder and president of the American Anti-Slavery Group. “Here you have a sophomore from Harvard, an African-American, who risked his life to go on an unauthorized flight that could have been shot down…[in order] to free slaves … .It’s just unbelievable.”

Along with four members of Christian Solidarity International (a Christian human rights organization based in Switzerland) and Joe Madison, a radio talk show host from Washington, D.C., Williams was flown to Zurich, then to Nairobi. There, the group boarded a small plane for the short flight over the Kenyan border and into a remote location in Sudan, where they touched down on a primitive landing strip.

“We went into a war zone,” Williams recalls. “It was very disturbing.”

Once on the ground, the group members were aided by some local Arab redeemers who have made their peace with the African tribes and agreed to go undercover to pose as buyers in the north and pay for the slaves’ freedom. “We went to a lot of different sites [where slave traders frequented], about five different places in a region of Sudan,” Williams says. There, the redeemers would purchase the slaves from their northern masters, using money supplied by Williams and his group.

The money comes from donations collected by both the American Anti-Slavery Group and Christian Solidarity International. The buyers pay about $33 in local currency for each slave. Factor in the travel costs, and the price for freedom is about $85 apiece. Jacobs estimates that more than 35,000 slaves in Sudan have been redeemed in this way in recent years.

Once the slaves are freed, many attempt to return to their villages, search for family members, and reassemble their lives. Some may eventually be recaptured. “A lot of the time there wasn’t a big happiness among the people [at the moment of liberation] because they’d been uprooted and taken from their land,” Williams explains. “They’ve been shoved around and didn’t really know what was going on. Their lack of excitement was definitely understandable.”

It was Williams’ responsibility to document as much personal history about each redeemed slave as possible. He tells the story of one young woman who had been taken from her home, repeatedly sexually assaulted, then forced to perform household duties for her abductors for as long as three years. Then there was the story of a 12-year-old boy named Yak Kenyang Adieu who had his fingers chopped off by his masters when he was too sick to tend the cattle. “Time and time again, I heard these same stories of utter brutality,” Williams laments.

“There is still a sense of amazement for a lot of people that slavery still exists,” Sage says. “The point [of Williams’ mission] was to document these people’s stories — to give them a voice. Jay is actually giving a voice to people who otherwise have no voice here.”

And Williams is hoping to project those voices across Harvard Yard and beyond. “Now the real work begins, to go and tell everybody that there is still slavery in the world and we have an obligation to do everything that we can to end it,” he says. “If we really live in a global community we have to fight these injustices.”

Calling the Sudanese slave trade a “threat to the blackness of all black Americans,” Williams has turned to fellow black students at Harvard for support. Several, including Tiffany McNair ’03, have been energized. “What Jay’s doing is a very amazing feat,” she says. “He has set an example that a lot of us need to follow.”