Fight over Huck Finn continues: Ed School professor wages battle for Twain classic

Mark Twain knew darn well what he was doing when he wrote “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn”: he was pokin’ at a beehive.

And for more than one hundred years, the bees have obliged, swarming out with criticism of the tale of the friendship between a poor white boy, Huckleberry Finn, and an escaped slave, Jim.

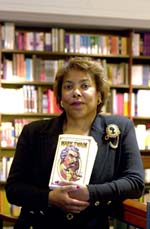

Amidst today’s debate on the book — much of which focuses on the repeated use of a racial slur by virtually everyone in “Huckleberry Finn” — is Graduate School of Education Assistant Professor Jocelyn Chadwick.

In April, Chadwick was asked to mediate a debate over whether “Huckleberry Finn” should be taught to high school juniors in Enid, Okla. The school board agreed to keep the book in the curriculum, but only if Chadwick returned in August to lead a workshop for instructors on how the book should be taught. She did and the book remains on the reading list for students.

Chadwick is one of the nation’s foremost scholars on Mark Twain. She has written a book on the subject, “The Jim Dilemma: Reading Race in the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” has made numerous television appearances to talk about the subject, and has traveled around the country lecturing on the value of teaching “Huckleberry Finn” to the nation’s high schoolers.

Though much of the debate over the book focuses on its language, other criticism takes aim at the use of the book to represent pre-Civil War America when other works — some by African-American authors — might be more appropriate in depicting America’s painful slave-holding past.

Whatever the reason, the continuing complaints about the book have landed it as No. 5 on the American Library Association’s “100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990-1999.” The “Scary Stories” series by Alvin Schwartz tops the list, released in honor of the Association’s 19th Annual Banned Books Week, which runs Sept. 23-30.

Chadwick believes “Huckleberry Finn” should be taught to students because it is an important work by one of America’s most prominent writers. It not only deals with a difficult time in American history, it marks an important transformation for Twain himself. Starting with “Huckleberry Finn,” Chadwick said, Twain’s writings stopped being just stories and began to reflect his social conscience.

But aside from the book’s importance in American history and in the study of Twain, it is also critical because of the debate it engenders, Chadwick said.

Race is one of the most complex issues in the country. “And we can’t talk about it,” Chadwick said. “Sometimes we need something provocative because it will spark conversation. Literature is a good way to do that because it keeps the subject at arm’s length.”

One of the difficulties in teaching “Huckleberry Finn,” Chadwick said, is that parents and teachers who object to its inclusion in the curriculum sometimes view the text through a lens colored by their own experiences, or by their community’s experiences, or by the strained present of race relations.

In Enid, some parents brought the town’s segregated past and their dissatisfaction with the present into the discussion about the book.

In Enid, some parents brought the town’s segregated past and their dissatisfaction with the present into the discussion about the book.

“You have to remind them you are there to defend the text and not to solve social issues,” Chadwick said. “One minister said Oklahoma has a problem putting African-American men in leadership positions. I said, ‘That’s not why I’m here. You can’t put that burden on me or on Twain. It’s not fair.”

Fair or not, race relations remain a touchy issue in America, and “Huckleberry Finn” has remained a lightning rod for criticism. The Pennsylvania chapter of the NAACP would like to see the book removed from required reading lists in high schools and colleges, though it doesn’t object to “Huckleberry Finn” being left as voluntary reading.

“The n-word is spoken there a number of times,” said NAACP Pennsylvania state President Charles Stokes. “The concern we have is that to a black child it might be damaging. Also to a white child, or a Hispanic child, those words could be damaging.”

Stokes said that the free use of a word so associated with hate and racial strife is inappropriate, particularly at a time when hate crimes are rising and race relations are fragile. Don’t teach the book, he said, or else update the language — as is done with the Bible periodically.

“What you’re saying is those words are OK, but they’re not OK to a group of people,” Stokes said, comparing the issue to that of flying the Confederate flag. “What the NAACP has done is take up a posture that the book as written is not good for America.”

The NAACP isn’t alone in its reservations about the value of “Huckleberry Finn.” University of Pittsburgh English Professor Jonathan Arac, author of “Huckleberry Finn as Idol and Target: The Functions of Criticism in our Time,” agrees that the book should be removed from required reading lists. Unlike the NAACP, Arac doesn’t think it should be removed from the curriculum entirely.

Teachers should only include the book in their lessons if they have a passion for it, if they want to teach it, and also if they have an understanding of how someone might find its content disturbing or insulting, he said.

Arac questioned the value of the discussion the book generates, saying the interracial goodwill the book illustrates in Huck and Jim’s relationship is squandered in racially divisive arguments over whether children should read it.

Arac also attacked what he sees as a common response to criticism of the book, saying supporters of “Huckleberry Finn” often have a dismissive attitude toward those who take offense.

“It’s as if no one who could read could read things negative in this book,” Arac said. “White authorities are telling black parents and students, ‘Shut up, you can’t read.’”

Read ‘Huckleberry Finn’ at 7

The issues dealt with in “Huckleberry Finn” are important ones to Chadwick, who traces her ancestry to slaves on both her mother’s and father’s side of the family. The Chadwick family, in fact, has regular reunions on the land in east Texas where their ancestors’ slave quarters once stood, land that was bought by Chadwick’s great-, great-grandfather and held for future generations. Chadwick also tells a story of a great uncle who was killed because he taught himself to read and write.

Chadwick got her first copy of “Huckleberry Finn” from her parents when she was a child. Active in the civil rights movement, her parents faced racially charged issues head-on, she said.

“My parents gave me ‘The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn’ when I was 7 years old, ‘nigger’ and all,” Chadwick said. “My father didn’t want to hide from anything.”In Enid, a town of about 50,000 in Oklahoma’s Cherokee Strip, “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” has been required reading for almost 500 high school juniors.

The book’s main detractors were an alliance of ministers from area African-American churches, who felt the book’s language demeans African-American students forced to read it. Ruth Ann Erdner, the school district’s executive administrator for curriculum and instruction, contacted Chadwick and asked her to talk to the community about “Huckleberry Finn.”Chadwick made her first visit to Enid in April 2000. She spent two days talking to Enid Board of Education members, students, state officials, members of the minister’s alliance, and the public.

Chadwick returned in August for the workshop, attended by 30 teachers from around the state. During the workshop, Chadwick discussed with the teachers classroom strategies, shared resource lists and working bibliographies, and spoke of the importance of preparing students for the book’s language and subject matter by talking about the era the book depicts.

“It was excellent. She was very thorough,” Erdner said. “I think she’s the reason the Board made the decision it did.”

Chadwick also suggested students be given an alternative if they find the book too objectionable, recommending “Iola LeRoy,” written by Frances E.W. Harper, an African-American woman, at around the same time.

“Iola LeRoy” is a story of a woman of mixed-race ancestry raised to think she’s white and then abruptly sold into slavery. Half the class could be assigned “Huckleberry Finn” and half “Iola LeRoy” to give students a chance to compare the works, Chadwick suggested.

Instead of providing a more sanitized version of the slave-holding era, though, “Iola LeRoy” uses similar language and deals with harsher issues, Chadwick said. She recommends it, however, because she believes good books should cause people to furrow their brows and seek out someone to talk to. That’s the job of literature, she said, and that’s what Twain achieved in “Huckleberry Finn.”

“You’re left with conundrums at the end of “Huck Finn.” You’re left with no answers,” Chadwick said. “Twain did not write a novel that’s meant to make you feel good.”