Photographer shares his Afghan experiences in two classes

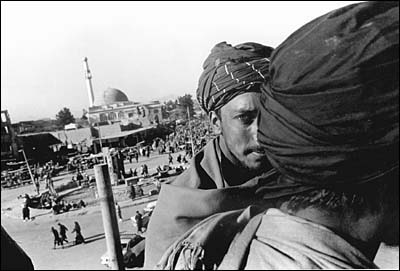

Edward Grazda has been taking pictures in Afghanistan since 1980, shortly after the Soviets invaded the country. He had been in India, but news of the conflict drew him northward until he found himself in Peshawar, the border town on the Pakistan side of the Khyber pass. It was there that he got to know Afghan resistance fighters (the mujahedeen or “holy warriors”) who agreed to guide him into the mountainous areas where the war was being fought.

He returned many times during the 1980s, riveted by the conflict between heavily armed Soviets and Afghan tribesmen who, until U.S. arms shipments began arriving, had nothing better to fight with than old-fashioned muskets.

But he was also charmed by the spectacular scenery and the generosity of his Afghan hosts. In 1990, he published a book of his photographs with accompanying text, Afghanistan 1980-1989 (Parkett/Der Altag, Zurich/New York).

Grazda’s last visit to Afghanistan was this past April. The experience was very different, and, from a photographer’s point of view, very frustrating as well.

“It was extremely difficult to photograph because there was a minder with me at all times, and you weren’t allowed to photograph any living thing, so if there was a person anywhere in the picture, even a hundred yards away, this guy would not let me take a picture.”

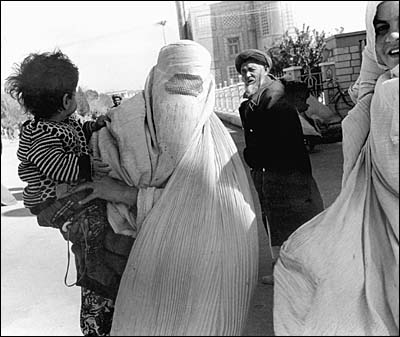

These new rules were put in place by the Taliban, an Islamic fundamentalist group that took over the capital city of Kabul in 1996. Their victory came after four years of civil war, following the collapse of the Communist government in 1992.

The Taliban’s repressive regime, which has been especially cruel in its treatment of women, claims to base its actions on a strict interpretation of Muslim law, a claim that Grazda finds hard to accept.

“For example, the ban on photographing people is supposedly based on the Islamic idea that you’re not allowed to make graven images, but it’s OK to have a picture on a passport or an identity card. And they carry this rule to an absurd extreme. For instance, you can’t have a picture of your dead father, even if that’s all you have to remember him by. If you do have one, you have to hide it.”

The restrictions that the Taliban have imposed on photographers illustrate what Grazda considers one of the key principles of his profession first, you must gain access.

“In my teaching, I always tell students, you can think of a great project, but the biggest problem is how to get access. You have to come up with a project you can actually do.”

Grazda is teaching two courses at the Harvard Summer School, Introduction to Still Photography and Documentary Photography. For his students, it will be an opportunity to learn from an experienced professional who for more than 20 years has used his camera as a way of learning about the world.

In his black jeans and gray polo shirt, Grazda almost looks like a black-and-white photograph. Low-key and down-to-earth, he strikes you as someone who has spent long hours on the periphery of events, downplaying his own presence the better to allow his subjects to be themselves.

Although he occasionally does assignments for newspapers and magazines, he defines himself as a documentary photographer, not a photojournalist. To an outsider, this may seem like an esoteric distinction, but to Grazda it is an important one.

“Photojournalists tend to go someplace for a short time, and the photographs they take usually come out in a newspaper or magazine relatively quickly. Documentary photographers tend to work on a project for a much longer period of time, and also they usually pick the subject themselves.”

They also have more freedom to cover a subject in their own way, to represent their own point of view. Grazda remembers spending time with the mujahedeen in the 1980s and noting the difference between his reactions and those of the photojournalists with whom he shared the experience.

“You’re sitting around eating rice and bread with these guys, and they’re telling stories or asking what it’s like in America, and the photojournalists are sort of disappointed because they’re wasting all this time and they don’t have a picture for the magazine. The magazine is only going to run two or three pictures and they want something burning or something blowing up or some starving refugee child in the foreground.”

But for Grazda, who thinks in terms of presenting his photographs in book form as a record of his personal experience, sitting around swapping stories with holy warriors who happen to be temporarily idle is a fine way to spend one’s time.

“It doesn’t worry me because the pictures are basically for myself. I don’t have to go back and show them to a picture editor who’s going to say, Uh-oh, you didn’t get that burning tank.’ I’d rather be in a normal, everyday place and just walk around and see what catches my eye.”

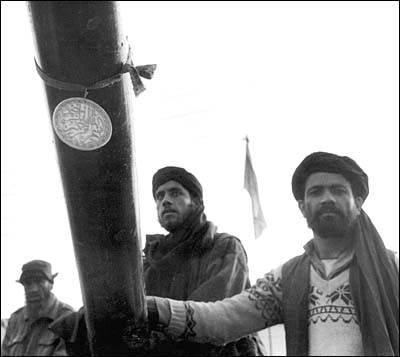

Grazda’s next book, Afghanistan Diary 1992-2000 (Powerhouse Books, due out in September), brings the story of this poor, backward, and war-torn country up to the present. While the first book reflected the exhilaration of the mujahedeen’s successful resistance to Soviet domination, the second one tells a much sadder tale, that of a war between indigenous political factions culminating in one of the most repressive regimes on earth.

In addition to outlawing photographs of people, the Taliban require women to be covered from head to toe (including a mesh panel over their eyes) whenever they go out in public. Women have been forbidden to work, go to school, or travel outside the home unless accompanied by a male relative. Because women doctors can no longer practice, and male doctors are not permitted to treat women, access to medical care for women has become almost impossible.

Grazda said that on his last visit he noticed that some of these regulations seem to be easing, but the situation for women is still severe, and adding to these problems is the fact that the country is experiencing its worst drought in 30 years.

Afghanistan is also going through its own version of ethnic cleansing. The Taliban are largely composed of the majority ethnic group, the Pashtun, and while the government claims to be broad-based, in actuality there has been widespread killing of other groups, especially those who speak the Persian-based language, Dari.

“My minder told me that he thought all Persian speakers should be killed,” Grazda said.

In view of the fact that the Taliban have effectively eliminated that all-important element, access, Grazda thinks his next project will be documenting the Afghan diaspora, to show how refugee Afghans are trying to preserve their culture in other parts of the world.

Grazda has been traveling the world with his camera since he graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design with a B.F.A. in photography in 1969. His first inspiration was his father, an amateur photographer who had been stationed in India and China during World War II. The photographs he brought back from these exotic places showed Grazda that there was a world beyond his suburban reality.

Since then, he has traveled and photographed in many areas, including Latin America, China, Burma, Thailand, Pakistan, and India. He finds that immersing himself in foreign cultures sparks his enthusiasm and creativity.

He also has found that the most exhilarating aspect of foreign travel encountering the unfamiliar and unexpected can be found in teaching as well.

“In photography, there are certain rules about things like developing film, but as far as taking pictures goes, I have no way of telling you what is going to be good or what is going to be bad, and one of the nice things about teaching is that students will come back and totally surprise you.”